In 2013, the Chinese government initiated the concept of the “Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road” (also referred to as the One Belt and One Road: OBOR) in tandem with launching the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in 2015, in which 57 countries have joined as members. OBOR is expected to exert multi-dimensional impacts on the global supply chain and maritime connectivity

OBOR aims “to promote the connectivity of Asian, European and African continents and their adjacent seas, establish and strengthen partnerships among the countries along the Belt and Road, set up omni-dimensional, multi-tiered and composite connectivity networks, and realize diversified, independent, balanced and sustainable development in these countries”.

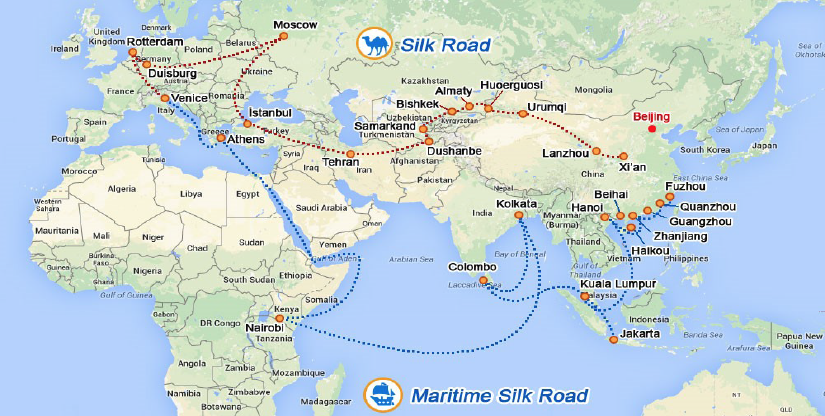

The map shows the overland rail route and the maritime route used by ships. The ports connecting the Maritime Silk Road are wholly or partially owned by Chinese interests.

China plans not only to connect inland cities to the Indian Ocean by rail connections to seaports on the east coast, but also to transport oil from Iran and Iraq directly to China by rail, rather than by sea. This would have an impact on container and liquid cargo movements in the Middle East and Europe, as well as on Shanghai’s transshipment trade through the Malacca Strait.

Norton Rose’s London-based global head of transport, Harry Theochari, is quoted as saying that “The Chinese will buy ports and infrastructure just about anywhere they possibly can” and “If you have control of a port, especially a box port for container ships, you are at a huge advantage”.

With the current glut of container vessel capacity in global markets, pricing for the overland route is twice as expensive as transport by sea, albeit somewhat shorter; it takes about 30 days from Europe to China by ship and about 20 days by rail. Political instability along the overland route could be seen as a drawback. The imbalance of trade flows between China and Europe could also see a lot of empty containers being railed back to Asia.

Some analysts say that China launched the OBOR initiative in an effort to find new markets for its domestic overproduction of steel and construction materials. A consortium led by the Chinese Railway Group is building a high speed train from Belgrade to Budapest on the condition that Chinese construction materials are used. Port-related construction also uses a lot of (mainly Chinese) steel, and most of the equipment used in ports such as cranes and heavy machinery is manufactured in China.

Others argue that the purpose of OBOR is geopolitical with Russia concerned about the influence that China will have over Central Asia. The establishment of the AIIB with a US$100 billion capital base in 2015 (US$738 million of it contributed by Australia) was viewed by Russia as a tool for expansion in Central Asia. Chinese President Xi had to work hard to calm Russian fears and assure Russian President Putin that Beijing has no plans to counter his country’s political and security dominance in the area.

The opening up of Iran and the recent lifting of sanctions will be beneficial for Iran as well as China and will assist in making the overland route a more viable option. More than a third of Iran’s foreign trade is with China, in fact China is Tehran’s top customer for oil exports. President Xi and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani recently agreed to build economic ties worth up to US$600 billion within the next 10 years.

China has vowed to expand its control of their supply chains in order to protect its export/import trade as well as their domestic trade. The government has allocated billions of dollars to achieve this goal. Most of this money will be directed towards projects in Asia, Africa and Europe but some has found its way to Australian shores.

In Australia, a Chinese company with connections to the government recently agreed to a 99-year lease deal with the Northern Territory Government for the Port of Darwin, much to the chagrin of the US Navy who has strategic interests in the area. The Port of Newcastle was sold to China Merchants and Hastings Fund Management in 2014 and a number of Chinese port companies have expressed interest in the proposed 50-year lease for the Port of Melbourne.

The China Investment Corporation (CIC) is also looking to have a financial stake in the proposed takeover of logistics company Asciano by Qube and Brookfield Ltd. The recent announcement of the establishment of a Chinese-backed shipping service between Australia and China with five Australian flagged container vessels is another example of increased Chinese interest in the Australian trade. The Australian investments are not directly related to the OBOR project but will assist Chinese companies in having more control over its supply chains.

Not everyone will be pleased by the increased presence of Chinese businesses in their countries, remembering an earlier wave of Chinese globalisation led by State Owned Enterprises. They made clumsy forays, and enemies, in such places as Africa and Latin America on a quest for oil, agricultural land and other resources. Many deals were politicised and some were corrupt. Hopefully, future Chinese investors abroad are more likely to be market-minded entrepreneurs than national champions.

Peter van Duyn

Maritime Logistics Expert

Centre for Supply Chain and Logistics

Deakin University